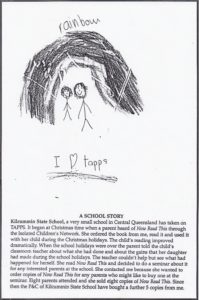

Use TAPPS to turn your reluctant readers into bookworms.

TAPPS – A teaching technique

TAPPS is a simple technique that is used when listening to someone else read. It is based on the philosophy that the thinking and reasoning required for learning to read need to be done inside the heads of the learners. Often we over-help by doing the thinking for them instead of letting them do it for themselves.

TAPPS defines the line between helping and over-helping. It is based on the author’s 3R’s: Rules, Risk Taking and Responsibility. It contains ten rules that are tried and tested. If the rules are followed, success follows. If they are ignored or changed, failure persists. You will find young or confused learners welcome the idea of thinking within the structure TAPPS provides with its ten rules.

All learners need to become risk takers to succeed with learning. This doesn’t mean they need to take unnecessary risks. It means they need to be put in the position of taking simple risks. For example, they say what they think a word might be rather than having someone else tell them the word. In many cases, they are pleasantly surprised because what they are thinking is correct.

Taking responsibility for oneself is one of life’s lessons for us all. TAPPS provides the learner with the responsibility of deciding whether to persist with working out a word or of asking for help. This is a simple choice with a very powerful result; the reward that follows when the correct word is read belongs to the learner. This simple shift encourages him/her to persist.

TAPPS requires the learner to read aloud. Reading aloud is the best way of deciding what a person’s reading is really like and where the problems lie. Children can look as though they are reading successfully when reading silently but, if they are experiencing problems, they are skipping words they don’t know and are probably gaining very little information or enjoyment from their reading.

TAPPS is all about accuracy. An example: The word “house” is different from the word “home”. They look different and, in many contexts, have different meanings. He made his home in Mexico. This means that he lived in Mexico. It doesn’t necessarily mean that he lived in a house in Mexico. If we allow children to say “house” when the word is “home” or to make similar errors, their brains are being fed confusing information. Brains need correct information.

TAPPS is used in the one-to-one learning situation. In this situation, the learner is given the undivided attention of the listener. If you are trying this at home, make sure you have allocated an area away from the rest of the family and from the distractions of TV, mobile phones and the like.

The minimum requirement to effect a change using TAPPS is twenty minutes a week. Ten minutes a day, four days a week, will make the change occur sooner.

Written records are kept of TAPPS. These are purely for the learner’s benefit. Often when children are told their reading is getting better, they don’t believe it. TAPPS records provide the proof this improvement is occurring.

TAPPS isn’t a magic cure but it does have a fairy tale ending! TAPPS requires time, patience, persistence, understanding, attention to detail, accuracy, dedication and, above all, the ability to follow a set rules composed by someone who knows the end of the story is “and they all lived happily ever after!”. BACK TO “NOW READ THIS”

If you have the time to read on, here are two case studies with happy endings. They are two of many.

POLLY

Eight-year-old Polly walked up the path to my office. She wore mirrored sunglasses, high heels and the latest gear which included a bare mid-drift top. She removed her glasses when she got to the top of the stairs, revealing sparkling eye shadow. Polly had arrived.

I began by checking what she knew about reading. She could say the alphabet, knew the letters’ names and most of their sounds. She recognised a few sight words, had absolutely no idea how to sound out a word and the resolve never to have to anyway. It didn’t take long for me to see her frustration and how she coped with it. She lost her cool and soon became a writhing, crying, screaming mess on the floor of my office. That was day one. She had come with her mum who placated her by offering her a visit to the shops on the way home.

I was surprised when Polly returned the following week. This time there was less make-up, the sunglasses had been left in the car and dad accompanied her. He began with a threat. If she misbehaved there would be trouble. This time I introduced Polly to TAPPS and also to my favourite reading series, Bangers and Mash, Book 1. I use this series because it is funny, it appeals to children and it is phonetically based. The author hasn’t sacrificed the sense of the story in order to include the phonic elements that are being taught through the story.

I introduced the structure of TAPPS before the lesson began. All went well until she encountered her first unknown word. I wasn’t swayed by her tactics to get other people to think for her and to provide her with answers. She tried to get me to deviate from my structure by smiling, batting her eyelids, making unpleasant comments about my wrinkles and finally by throwing herself on the floor and having a good-sized tantrum.

Polly continued to cry, then whimper, sob and finally just sit there. I reminded her of her choice to have a go at the word or to ask for help. She finally got up and sat on her chair. We sat there for a good ten minutes.

She had a go at the word. Under the rules, I told her the parts she had correct and she worked out what it was. She was elated. The going wasn’t easy but we persisted. My patience was tested more than once. I taught her the skills she didn’t know; how to decode words, phonic rules that she had been taught but which she had never internalised. After a while, her reading became more fluent, her sight vocabulary increased as the books she read increased in difficulty and, eventually, she rarely needed to decode words at all.

Polly caught up to her peers. She could listen to instruction and was open to learning. In fact, her true, delightful, better-dressed self began to emerge. Her parents were happy with her progress and could finally see she had a future as a reader and a learner. They also began to like her more than they had. They had simply given in to her to have some peace.

I have included Polly’s case first as I have encountered quite a number of students who have had her attitude towards learning. They have an expectation that learning should be easy and instant. If it isn’t they can’t cope and throw tantrums. Learning does require effort. Even the very best in the class usually have to put some effort into learning. They have to listen, follow directions, and conduct themselves in the way that learning demands. What makes them different from Polly is they have some built-in self-discipline to apply to learning. She took the opposite tactic and just kept running head first into trouble. TAPPS helped her find the way to freedom with learning she yearned for but found impossible to achieve on her own.

ANDREW

Andrew was twelve when he first came to my office. He announced that he had never read a book and really didn’t see the need to read one ever in his life. His ability to act showed its head early and I could see his need to read was crucial if he were to follow his passion. Once again, our first encounter was really to see what Andrew knew about reading and he already knew more than he realised. His reading age was about eight. He had a limited sight vocabulary, so he didn’t have to stop and decode every word but there were quite a few that eluded him when I listened to him read at this level. He could sound words out and had a good knowledge of phonics that he had acquired from the many programs he had attended in his efforts to become a reader. He was having difficulty, however, in piecing together the knowledge he did have so he could actually sound the words out successfully.

Andrew told me at this first interview he was often called on to look after the office at school and to organise events at which he would be the announcer. He had already appeared in plays. He did all of this on sheer personality and ability to memorise, rather than to read.

Andrew’s path to me had been a rocky one. He had had problems early in his school life with all of his learning. He had been tested and re-tested. At one stage he had been put on Ritalin for a period of two years but it hadn’t had the desired effect. Family life was in a bad state. Andrew, the eldest, was giving everyone a bad time.

He confided in me much later on that he had begged his mother not to bring him back to see me after our first encounter because I made him think. Obviously, his mother took no notice of him and he returned for two lessons a week, one for language and one for maths.

Andrew’s dad accompanied him to lessons for several weeks so he could learn TAPPS and help him at home. This he did for the first couple of years into Andrew’s instruction. After that, he could read for himself and no longer needed his dad’s input. We began by reading a book at Andrew’s reading age of eight. It wasn’t at his interest level but it had the look of a book his peers might be reading. There were no pictures to accompany the text and the text was divided into chapters. The book had a spine and the print was the size print that his peers might be reading. Andrew was reluctant, but by the end of the book he was really doing quite well. We had been able to piece together his phonic knowledge so he could draw on this knowledge when he needed it. His sight vocabulary was increasing. His reading was becoming more fluent.

This initial improvement encouraged me to find a novel for Andrew to read next. With the help of a bookshop attendant, I chose A Genius in the Family which is the story of Jacqueline Du Pré, a famous musician. Andrew took to this novel like a duck to water and soon he was reading most nights to his dad and to me once a week. The vocabulary presented him with some problems. It wasn’t easy but he persisted, as did his dad. I gave Andrew lessons in dividing words into syllables to assist him with decoding longer words. I also told him the meanings of words with which he wasn’t familiar and began his instruction in looking up words in the dictionary in order to find their meanings for himself. From here he began to take some control and began borrowing Agatha Christie’s novels from the library which he read for himself. From these novels he went on to his favourites, biographies and autobiographies.

When Andrew’s dad and I listened to his reading early in the piece, we weren’t expecting perfection. We were both willing to listen to his reading and to help him as he needed it. If that meant helping with most words in some sentences, then that was what we did. We all stuck to the rules of TAPPS.

Andrew continued his lessons with me throughout his high school years, long after he had become a reader. He was assisted by his teachers at school and by their specialist support staff. The last I heard, Andrew was studying at university to become a teacher of art and drama. BACK TO “NOW READ THIS”